In this section of the virtual exhibition, you will be introduced to findings from the arts-based research project, “Expressions of abuse and agency: Art-making addresses human rights violations in the Australian Criminal Legal System.” This project is part of the “Phenomenology of Violence: Investigating Subjective Experience of Violence for Justice Theory and Practice” project at the Justice Health Program, UNSW, Sydney.

Please note: These findings come from interviews with the 9 art workshop participants conducted within two weeks of the workshop. The findings express the views of these individuals who have extensive experience of the Australian criminal legal system, including incarceration.

Introduction:

In this arts-based research we sought, through engagement with art and stories created by people with lived experience of incarceration, to reveal really seen aspects of what happens in Australian prisons. After in-depth interviews with workshop participants and data analysis, findings were divided across two sections: Experience of the Workshop, with four themes, and Experience of Incarceration with six themes.

Arts-Based Research

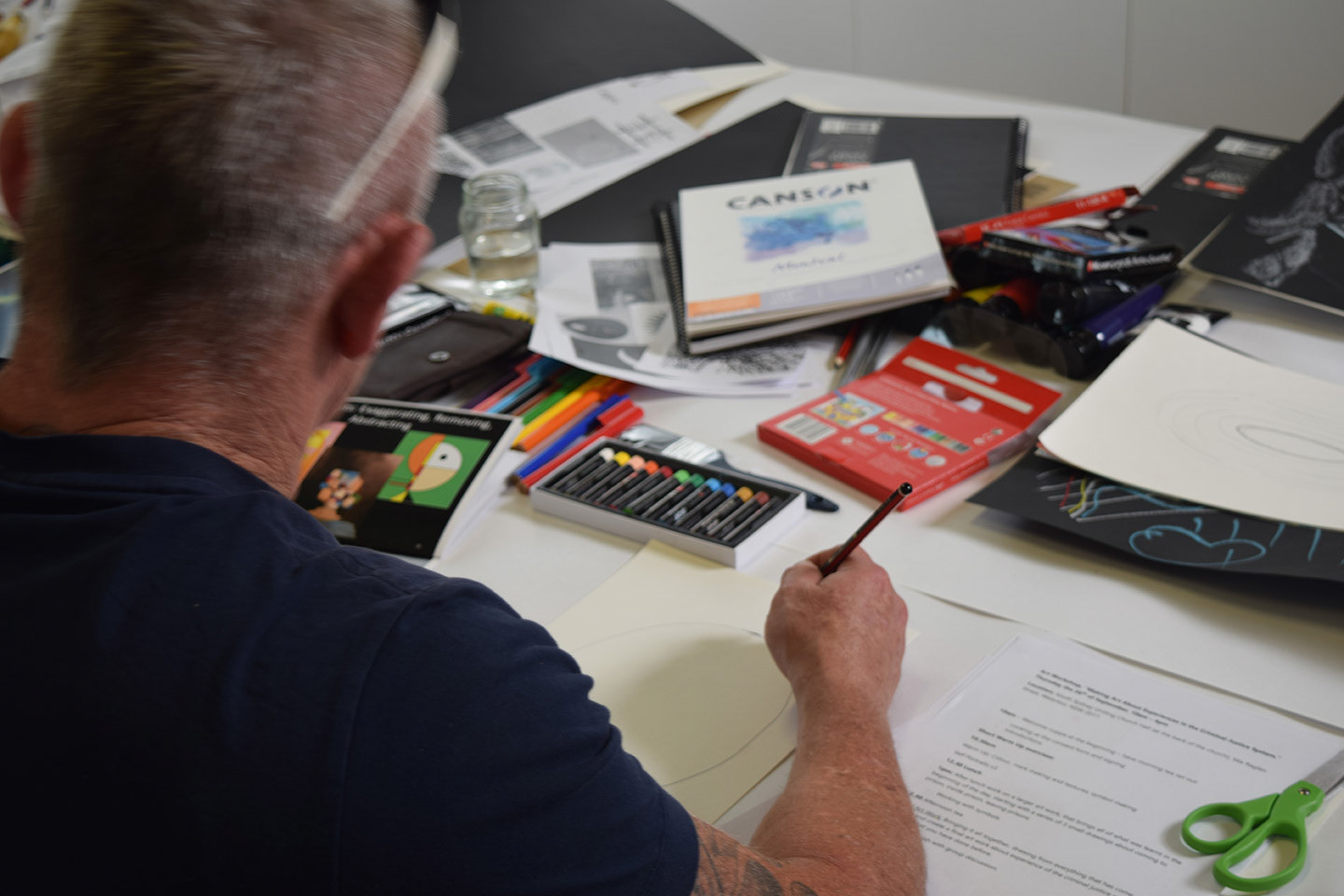

Art-making as research offers important insight into subjective or phenomenological foundations of lived experience (Woodgate et al., 2020). Additionally, the therapeutic aspects of art making are well known (De Witte et al., 2021; Schouten et al., 2015; Slayton, D’Archer & Kaplan, 2010), and there has been a long history of carceral art (Cox & Gelsthorpe, 2012), including art therapy programs in prisons (Cheney, 1997; Edwards, 1994). Research on the benefits for justice involved individuals of participating in art making focuses on the way that it offers a means for incarcerated individuals to describe and address what is difficult to put into words (Visse, Hansen & Leget, 2019).

The making of personally meaningful images is therapeutic as it can generate self-insight, bring suppressed feelings to the surface, and support the development of agency (Johnson, 2008). As such the heightened self-awareness that can be gained through art making then underpins personal growth, healing and increased social awareness (Seidel et al., 2009). Art making can also be thought of an act of critical resistance (Kelly, 2022) particularly for those who are, or have been incarcerated. For as Kelly (2022) emphasises, the development of self-worth and agency provided by art-making, works as a ‘counter weight’ to the experiences of dehumanising conditions that criminal justice involved individuals often suffer.

Context and Demographics

It is important to know the context of participants lives when seeking to understand their involvement in the criminal justice system. While poverty and abuse were the foundation of many of the participants lives, there were other issues such as adoption, being an immigrant or refugee, having health problems as a young child, such as a serious hearing problem or a serious accident, being extremely sensitive, and for all of the participants, suffering diagnosed and undiagnosed ADHD.

A brief overview of this context is introduced here starting with participants demographics:

One woman and eight men attended the workshop, they ranged in age from 46-82, there were four Aboriginal participants, three born outside of Australia, and three white Australians. The time they spent in prison ranged from nine and a half to thirty-four years. Many suffered ADHD-type symptoms, mental ill health, and addiction issues, many had experienced abuse in their early lives, and all bar two came from rough violent homes or violent areas.

One woman and eight men attended the workshop, they ranged in age from 46-82, there were four Aboriginal participants, three born outside of Australia, and three white Australians. The time they spent in prison ranged from nine and a half to thirty-four years. Many suffered ADHD-type symptoms, mental ill health, and addiction issues, many had experienced abuse in their early lives, and all bar two came from rough violent homes or violent areas.

Describing their early life one of the participants said

From a very young age, growing up where I did, there were always neighbours squabbling, fights, breaking windows, having stuff stolen from our home, anything, of any good value, just stolen. And then I would get picked on, bullied, and bashed at school. Plus, my Mother had mental health issues that were never addressed.

Another spoke about ‘getting out on the streets’ at a young age

You know, we'd all go out stealing cars and stuff like that together. We used to see our brothers get into crime and fights and stuff like that, and that was just a normal for us. Soon as I was able to go to boys’ homes I was in there, and yes, I was abused in there. Basically, I grew up in stolen cars and which ended in jail and, and then the cycle of recovery.

Abuse and trauma in childhood was a significant aspect of the context of participants lives The five participants who had been in juvenile detention also experienced multiple forms of abuse including sexual abused in those centres. Describing his experience in juvenile detention this participant explained that some places were worst than others, “I was hurt in those places, and some were worse than others, but Tamworth was the worst one. They beat you when you first arrived, and you were given a bucket to shit in.” The negative impacts of this abuse stayed with participants including when they went through the compensation process. As this participant explains, “It took years to get the payout. Yeah, it brings it all up again when you have to ring the Psych and do the interviews and rehash the situation. So, I'm glad it's over and done with now. Though it’s still not over and done with, you know what I mean?”

Section 1: It’s a sad sorry story: Experience of incarceration

Overview:

Findings from “Section One: Experiences of Incarceration,” divided across six themes, starts with the theme - “The Jail Attitude,” a hypervigilant state that had developed in jail and stayed with participants for many years after leaving jail. Alongside the jail attitude some participants spoke about the sense of having lost their lives through incarceration, and an ensuing loss of hope and depressive episodes. The second theme focuses on the physical abuse all the participants said they suffered at the hands of prison guards. Despite this contravening Rule One of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, it was regularly reported by participants. Themes three, “Overcrowding and Understaffing,” Four, “Prison Food.” and Five, “Health Problems,” relate to serious problems in these areas of basic physical care. All participants spoke about experiencing overcrowding where they were in cells that held more people than they were designed for, and some had experienced being locked in cells for 23 hours a day, because of staffing problems. They spoke of how prison food was inedible, and that they had suffered inadequate health care. The last theme, “Impacts of Imprisonment” details negative psychological impacts of imprisonment that one participant described as the sense of ‘never being free.’

The ’Jail Attitude’

When asked what the worst thing about being in jail was, a participant said “watching people die.” He and other participants spoke of the way the violence and abuse they witnessed and suffered in prison led to ongoing chronic stress, anxiety, and hyper-vigilance. A participant described this as the ‘jail attitude,’ which he and others spoke of having in and outside of jail. He described it as “always being on,” Outlining the meaning of a self-portrait that had many eyes, a participant explained how the ‘jail attitude’ lingered, and was exacerbated by the constant surveillance he had been under, he said:

It's not looking in one direction, because I was watched from every direction, it didn’t matter where I went. It’s hard to forget that you weren’t allowed out of the yard without getting escorted. Now when I move house the Police check on me,…and even now I’m not free because I can’t go anywhere without permission.

Participants spoke about a loss of hope in prison, and for some, how they used drugs to deal with the anxiety and depression they suffered. A participant who began using heroin in prison, said, “it was good, just made you forget that's it.” Participants who’d had long prison sentences struggled with depression because of their sense that prison had taken their life. This was aptly described by a participant who said, “My body is in its 60’s but my heart and mind are only 20. Yeah, my body's starting to break down, and my mind and heart can't keep up with.”

Participants outlined several reasons they felt tense and anxious in prison. Some spoke about how there were many people who shouldn’t be in prison, explaining this a participant said, “A lot of people that make up the prison population now have mental health issues. They should not be there; they should have their own facilities. It can make it dangerous because officers don't come on the floor much.” For other participants it was ‘mind games’ they felt guards taunted them. These mind games led to a build-up of tension and “there's no release of the tension, and there's no punching bag there that we can take it out on, so it gets to a point where it all builds up and you just let it go.” Describing this further he said:

When I first came in all the mind games were all new to me. I didn't know what was going on, or how it happened, and all the things were scaring the hell out of me. It got to a point so much where they were pushing me, prodding me, and doing all these things to me, that I pushed the officer out of my room, and smashed it up rather than smashing him.

A participant spoke about a ‘mind game’ played by prison guards in which they would incite racial tension. Describing this he said, “officers caused racial tension, you know, they'd go up to a Lebanese bloke and say, I called you a wog, and then they’d go to an Aboriginal bloke, and say he called you black.” Participants spoke of petty mind games where their showers were turned off by guards before they had finished, phone calls were cut off mid-call, letters to loved ones weren’t sent, and visits by family were cut short for no apparent reason. Verbal abuse by prison guards was common. Participants spoke of guards using abusive language including name calling. A participant detailed some of the names he’d been called, “Boy, motherfucker, hey cunt do this, do that.” Here another participant speaks about verbal abuse:

We had a female senior officer come down to our common room and make us all stand outside our doors. Now, I thought it was just going to be a general lecture about behaving ourselves. But she ripped into us, she said things to the effect of, “I don't care who raped you. I don't care if your father or your grandfather molested you, you will pull the fuck up, because I don't give a fuck what's happened to you.

Physical Abuse

In addition to the ‘mind games,’ all the participants described physical abuse in prison. While they spoke about violence committed by fellow prisoners, what was more regularly described was the violence they suffered at the hands of prison guards:

You could get dragged into a cell and flogged at any time. You could be woken up at one, two in the morning and be in Grafton jail, and the next morning you'd be in Goulburn jail. So, we used to call it getting Shanghaied, and you wouldn't even get to pack your own stuff up, they'd pack it up. And when you got to the new jail, half your things would be missing, and so you're always on your toes.

Some of the participants spoke of becoming a target for guards and if this happened they experienced more abuse than others. This was described by a participant who had mental health issues, and who felt he had been targeted:

Oh, yeah, the squad were running in and that’d bash you and that…Yeah, they’d grab you whenever, strip search you, looking for anything. Then it stopped, the Psych told them, if they kept running in, that I might sneak up on ‘em and attack them when they're not looking. So, they stopped, and I asked them. I said, ‘why don't you throw in anymore?’ They said the Psych told us how crazy you are,’

Explaining what ‘throw in’ means this participant said, “they run into your cell and bash you. Usually, they’d run in at night.”

Overcrowding and Understaffing

Describing major issues with Australian prisons this participant put it succinctly, “they are overcrowded and understaffed.” Speaking about overcrowding another participant explained that there were: “six out in a four out cell or something like that. Yeah, four beds and two mattresses on the ground…you get a mattress on the ground, and there's one toilet in there.” Another participant described how cells meant for two people (two out) had four people (four out) in them, “they started making two outs into four outs, and the shower would run directly over one of the beds with no extra ventilation, and the toilet would flush by someone's head.” Overcrowding has several negative implications, including the spread of infectious diseases and blood born viruses, plus it is another element that feeds into the unceasing tension that people in prison can suffer. As a participant said “if you don’t have the right roommates there can be tension.”

Understaffing was identified by participants as another serious problem. Because of a lack of staff, people in prison could be locked into their cells for up to 23 hours a day, and in some cases for many days in a row:

When they were short of staff or whatever, they’d lock you in, you know. They can have Segro downstairs and normal upstairs, and once you're all locked in, you're all in the same boat, you know, but Segro, you don't get out at the end of the day, or when the staff come back. It could be for days; there’s a toilet in there but no shower.

Prison Food:

Describing the food in prison a participant said, “It’s pretty much inedible.” Describing why the food was inedible this participant said, “Some of the dinners, like, there's that much water in it, like from being frozen, then heated down and then frozen again and then reheated again, yeah, and it's like water. It’s not healthy, and looks like something you’d throw in the bin.” Another participant spoke about how he was always hungry because:

The food was horrible. It's just like, they're just frozen meals that have been there forever. You just look at it, and go, oh my god I can’t eat that. Yeah, you don't get your nutrition, that's for sure. I was hungry, always hungry. Yeah, especially if you haven’t got someone looking after you outside, you’re stuffed!

Participants who were financially supported by friends or family, or who had money from the work they did in prison had access to ‘buy up.’ Usually, once week they could buy food and personal items with their own money. A participant spoke about being able to avoid prison food after he purchased a rice cooker, “I didn’t eat the food, I had a rice cooker, and I’d get rice and whatever else I could buy in jail, and make kind of like a fried rice, bamboo shoots, and mushrooms. If you don't want to eat the jail food, you buy your own stuff on the buy up.”

Health Problems

Many of the participants spoke about inadequate health care in prison, here a participant speaks about the long wait to see a dentist and how the dental work that was eventually done led to serious complications:

I broke a tooth. I had to wait for a month, I was walking around with a broken tooth. The dentist filled that tooth, but within a day it came out again. Upon my release, and being able to see a dentist outside, I found out the reason I had pain in the back of my mouth and tooth for two years, it was because I had a massive air pocket under there!

This same participant described how they didn’t get any help with the eating disorder they suffered, and how if treatment was questioned, including any medication that was offered, then they were refused further treatment:

You won't get help for an eating disorder; you end up in a mental health cell. Yeah, you'll be given Seroquel for everything. Or a Panadol. They tried to give me medications, but if I refused them because they couldn't prove that they were necessary, I was told never to write a form to see a psychiatrist again. But they didn’t have a proper diagnosis for me, so they can’t just give me a tablet.

It appeared that health care varied across prisons though several of the participants spoke of being offered Panadol for almost any health problem. This participant explained how, “some jails are more neglectful than others. I've definitely seen that you know, if they're in a lot of pain and they just give you a Panadol. They’re not gonna do much, if you had a broken leg, they'll just give you Panadol.” Participants spoke about being persuaded to go on certain prescription medications to help with their chance of parole:

I didn't really get on the ‘done’ until two years before I was getting out. I said, ‘I've been in here for years, and now you’re putting me on the methadone?’ They said, ‘you want to get out, jump on it. You go to the clinic now and jump on it.’ I thought, alright, I’ll get stoned for a little bit. Soon as I got out, I jumped off it.

Another participant had a similar experience, he was advised to have the buprenorphine injection to give him a better chance of parole, which he questioned as he had been addicted to methamphetamine. Though in the end he had the injection. When this participant left prison, he had to withdraw from the buprenorphine by himself because there were no support services available. Another issue with health services in prison was the inability for some participants to get medication they had been on before going to prison. As this participant explained about a medication he’d used for some time, “Yeah, it's not a medication that you can just jump off either. You know, it's just they usually give the Seroquel to people with schizophrenia. That's why I don't understand why they put me on it for depression, I was on Avanza, then they swapped me to that?”

Impacts of Imprisonment

People in prison are some of the most vulnerable people in society and often come from disadvantaged backgrounds. People who spend time in prison experience higher rates of homelessness, unemployment, mental health disorders, chronic physical health conditions, communicable disease, tobacco smoking, high-risk alcohol consumption, and illicit drug use than the general population (AIHW, 2023).

The quote above alludes to the negative impacts of imprisonment, which the participants add to here with a focus on psychological impacts of imprisonment. As described earlier participants spoke of living with the ‘jail attitude,’ or anxiety and hypervigilance. This participant spoke about how they still get triggered, “I had a psychiatric report done when I got out, and I know that I get triggered more even than my normal PTSD. I know that I have an adjustment disorder.” This participant also spoke about struggling with authority outside of prison because they had to fight so hard in prison to get the help they needed:

I struggle with authority still, because I also have issues with just going to things like Centrelink, because I will react and I will jump to a more aggressive reaction. Because I had to learn to sort of jump to my own defence in jail. So, I had to be very quick to stand up for myself to get something.

Another participant spoke about being ‘broken’ by prison, he said, “oh, just that it’s a bad place, and I don’t want to go there again. It really broke me, because some stuff that was going on outside. Just, you know, losing relationships and stuff like that, losing my kids and stuff.” A participant who had spent a lot of his life in juvenile detention and prison struggled to feel a part of the community, which he explained saying,

The majority of my life was in jail or boys’ homes and psychiatric hospitals when I was a kid. But the thing is, the system let me go, and didn't really let me be nurtured and grow properly in a family environment. So, I don't know really what a family environment is, but I know that a family environment is better than being in a lock up, because that helps you to isolate yourself from other people, or from the community.

Despite being freed from prison participants spoke of the sense of ‘never being free,’ or of the ‘mind games continuing.’ For some this was an ongoing psychological condition, for others, who had lengthy parole conditions, they were regularly monitored by the police. As one participant affirmed, “I’m never free, I can’t go anywhere without permission.” Others felt they were targeted and unfairly treated by the Police, as this participant said, “You know you’re trying your best to not get into the trouble. Then they come around, do bullshit charges or whatever. You know, petty stuff. Yeah, trying to charge you for jaywalking, or smoking in public.”

Section 1 in conclusion:

In this section of the findings about experiences of imprisonment, participants clearly outlined how the violence, physical and psychological abuse, overcrowding, unpleasant food with little nutritional value, and inadequate health care in prison negatively impacted them. Leaving them with chronic stress and anxiety described as the “Jail Attitude.” Much of what they described and made art about contravenes the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, also known as the Nelson Mandela Rules. The participants art and stories have revealed aspects of the Australian prison system that are rarely seen – a system that one participant aptly described as a “Sad, Sorry Story."

Findings 2: It’s another way of dropping your baggage: Experience of the workshop

The four themes in this section about experience of the workshop offer important information for human centred, criminal justice theory and practice.

Overview:

Findings from “Section Two: Experiences of the Workshop,” divided across four themes, starts with the “Reasons for Attending the Workshop,” which emphasises the need for people with lived experience of the criminal legal system to connect and share. This theme also outlines the need for self-expression, therapeutic interventions, and ways to inform the public about the harms of incarceration. Next the “Experience of the Workshop” theme shows how process art workshops can provide a much-needed space for justice involved people to have creative outlets, and be involved in practices that provide opportunities to reflect on their lives. Theme Three, “Drawing Change,” which explores art practice as a means to describe feelings, memories and experience, highlights ways participants eloquently used colour, form and symbols to develop an important personally meaningful symbol language. Theme Four, “Outcomes and Realisations,” describes the way new meaning arose for participants as they worked with Process Art. Gaining this new meaning can be very important for individuals healing and reintegration.

Reasons for Attending the Workshop

Participants outlined different reasons for coming to the workshop, ranging from it being recommended by their psychologist because of a recent depressive episode, or as a means of expression. For fellowship with others who’d experienced incarceration, and to help raise awareness about incarceration. Describing the latter this participant said:

I like to help people who’ve never been in custody, or have never had a loved one in custody, to understand what it’s like. I want to contribute my views and opinions and share that information with people so they can get a better understanding, as much as I can.”

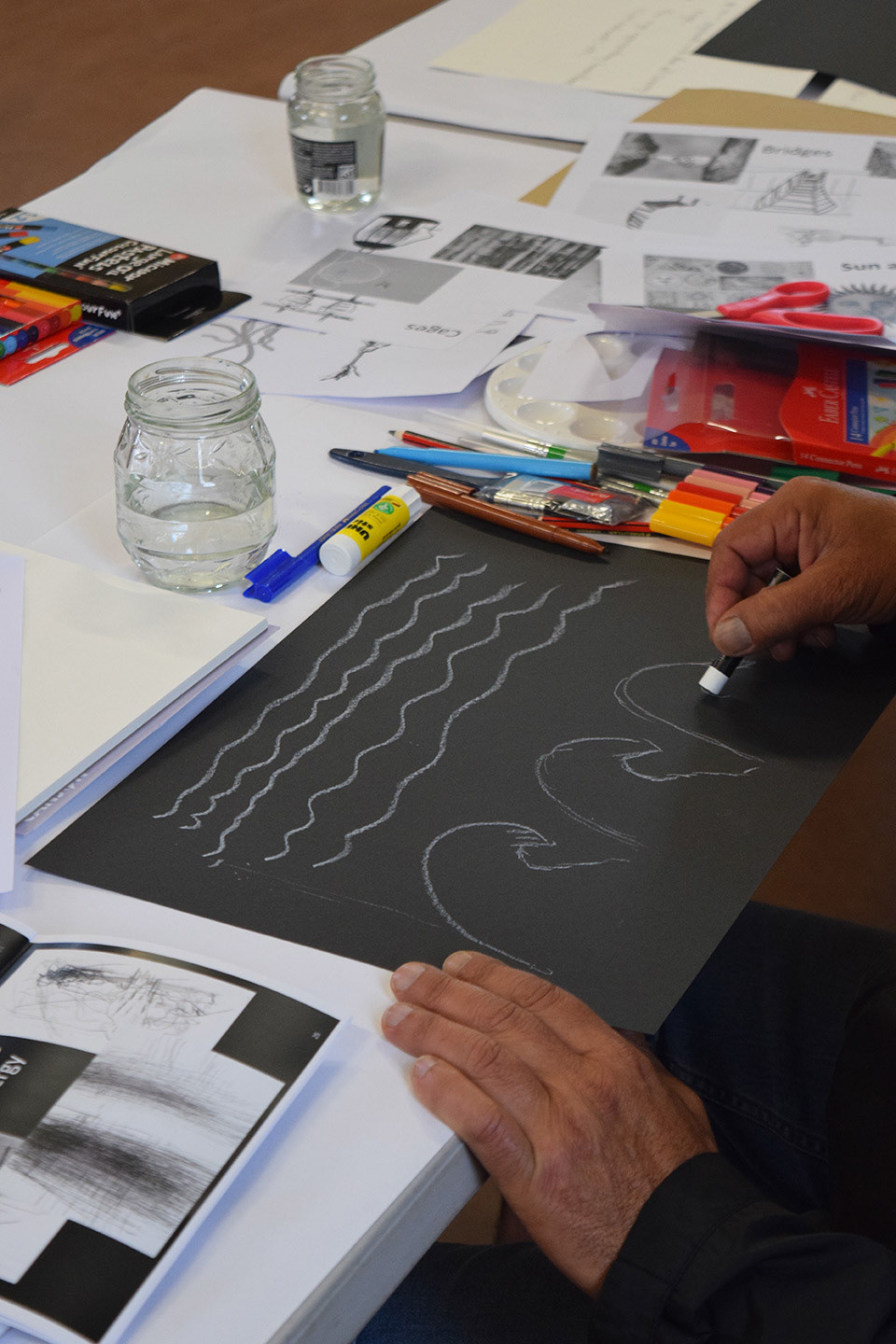

Experience of the Workshop:

Participants spoke positively about their experience of the workshop, saying they enjoyed expressing themselves with art mediums, and being with other people who understood them because of their shared experience of incarceration. Describing why he liked the workshop a participant said: “It was a good class. I enjoyed it, and I gave you what I knew of myself. And it also gave me a chance to express myself and hopefully it will help people understand now who I am.” Another spoke of the workshop offering a contemplative space in which the making of, and reflection on the art works enabled them to gain an overview of, and insight into the trajectory of their life:

I really liked the crayon drawing where it was about the earlier years of your life till now, or your journey. You could see what was going on without it being too pretty or great. I could see what was sort of going on for me in my life through it. So, I really enjoyed that.”

Some participants struggled at times during the workshop because of health issues. A participant with traumatic brain injury found the last and longer art work of the day difficult to complete because of his brain injury. He said, “towards the end I just felt really tired and worn out; you know at the beginning I was all guns blazing, but because of my brain injury, I've got, like, memory problems and I got tired, but I still wanted to finish the job.” Another participant who has ADHD felt he couldn’t keep up with the shorter practices, he said, “if I concentrated too much on what I was feeling, my mind would go everywhere. So, I tried to get a picture in my head and do that, otherwise, it was all over the place.” He, like some of the other participants, initially struggled with the preliminary shorter practices, feeling that they didn’t have enough time to complete them. However, after reflecting on the workshop several realised the benefits of the workshop’s scaffolded structure, which was described by this participant:

So, I didn't really understand why we did the smaller exercises. But when we did the one in the afternoon, it made sense to me, because I could put the big one together easily by using parts of the smaller ones. So, then it dawned on me, made sense that, ah, that's why we did all of these small exercises and learn different shapes, forms, lines and, you know, words and stuff and pictures, and in the end, it told my story and a true story… and I'd love to continue with it, and I will. I've brought my pastels and book home, and I did some more art last night”

All the participants spoke of enjoying being with others who had experience of incarceration, and how they would like to attend other similar art workshops. This was because of the camaraderie and opportunity to speak freely with others who understood them. The pleasure and benefit of spending time together was also emphasised when participants spoke about how they enjoyed the group sharing at the end of the workshop. As this participant explained. “I liked it because you can put input into other people's work, and they seemed to like that. I liked the last one when he read the words he wrote on his art about how he had struggled but ultimately felt good about himself.” Another participant spoke of how when fellow artists spoke about their art works it helped him, “you see the actual soul that they’re putting out there. So, it gives you a different perspective on who they think they are and who you really are. It’s a good thing too, because it helps open you up. It was like they ripped off their masks.” Lastly, a participant described how when listening to other artists describe their art works it helped her understand them through their art. She said, “I liked the group discussion very much, because I got to understand their art, if I'd just looked at some people's art I wouldn't have had a clue. Yeah, it was great to hear what their pain was, and about their experiences.”

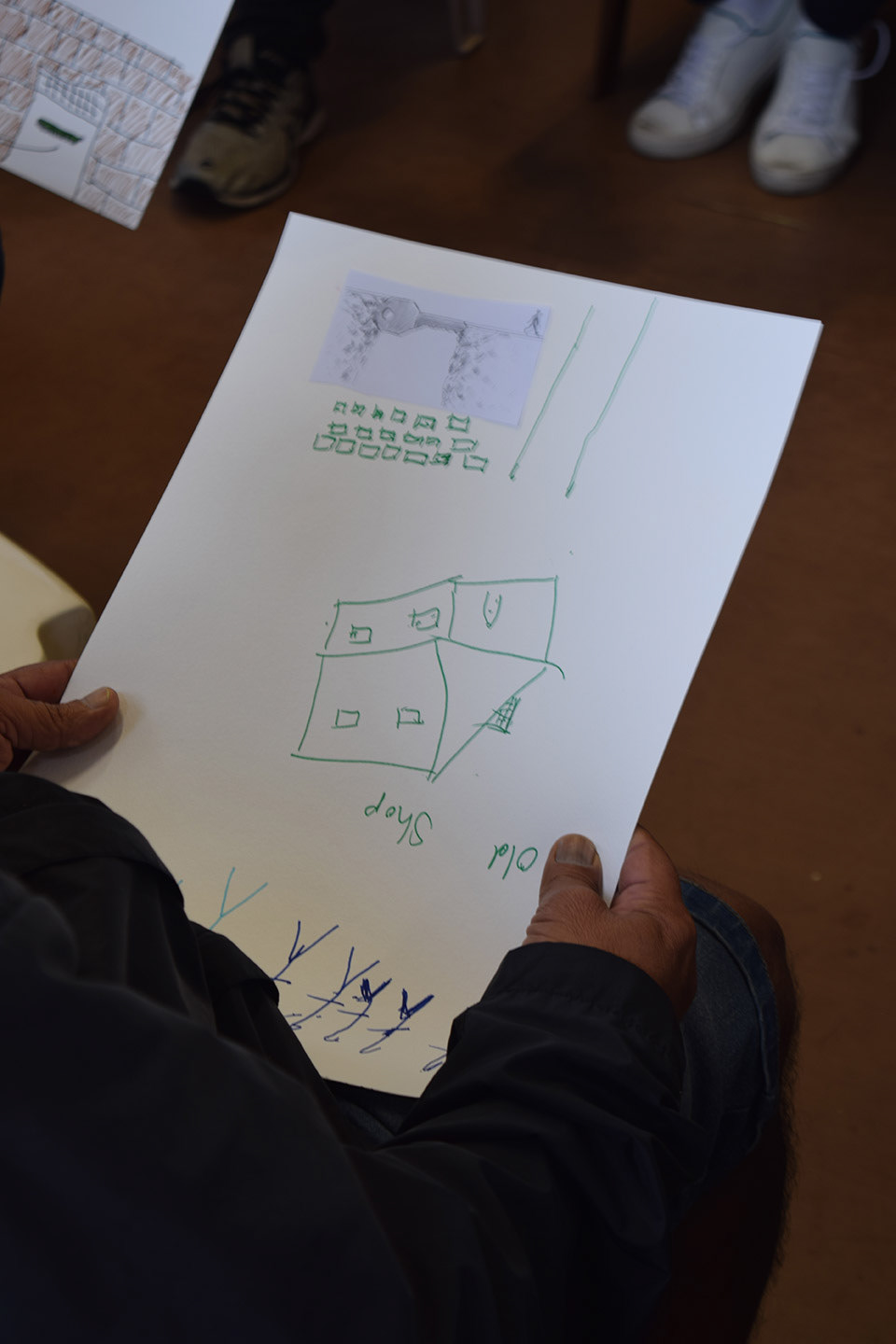

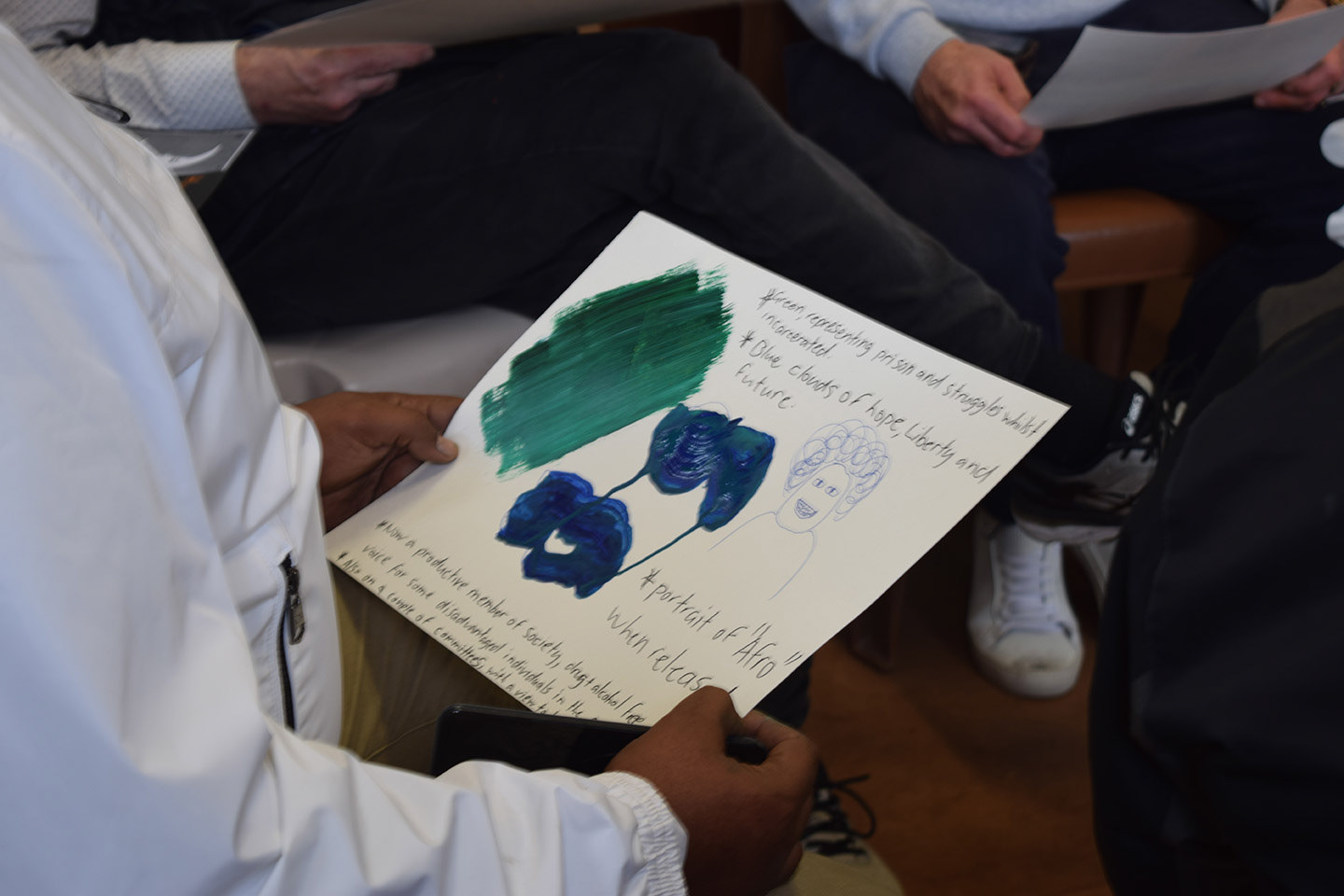

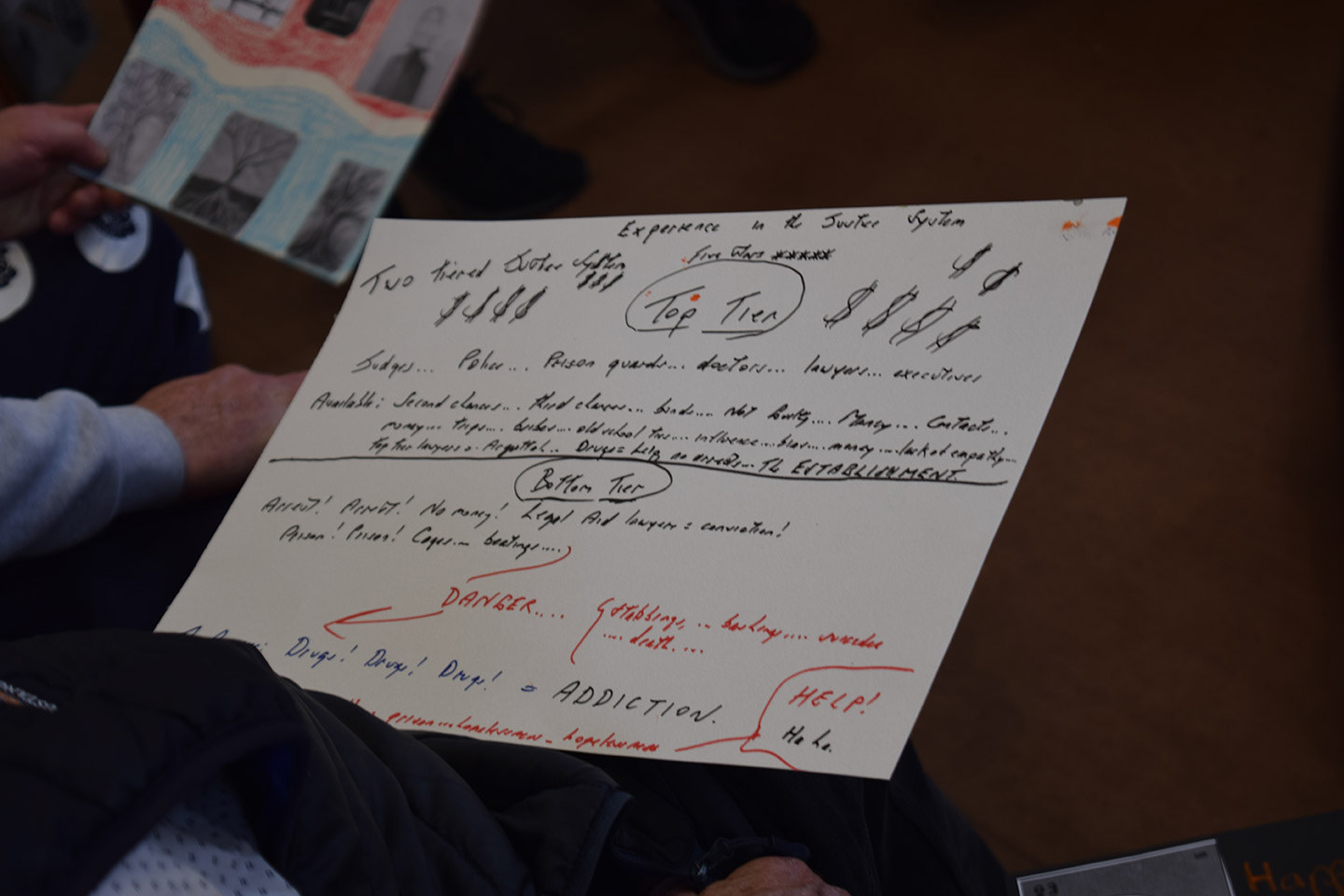

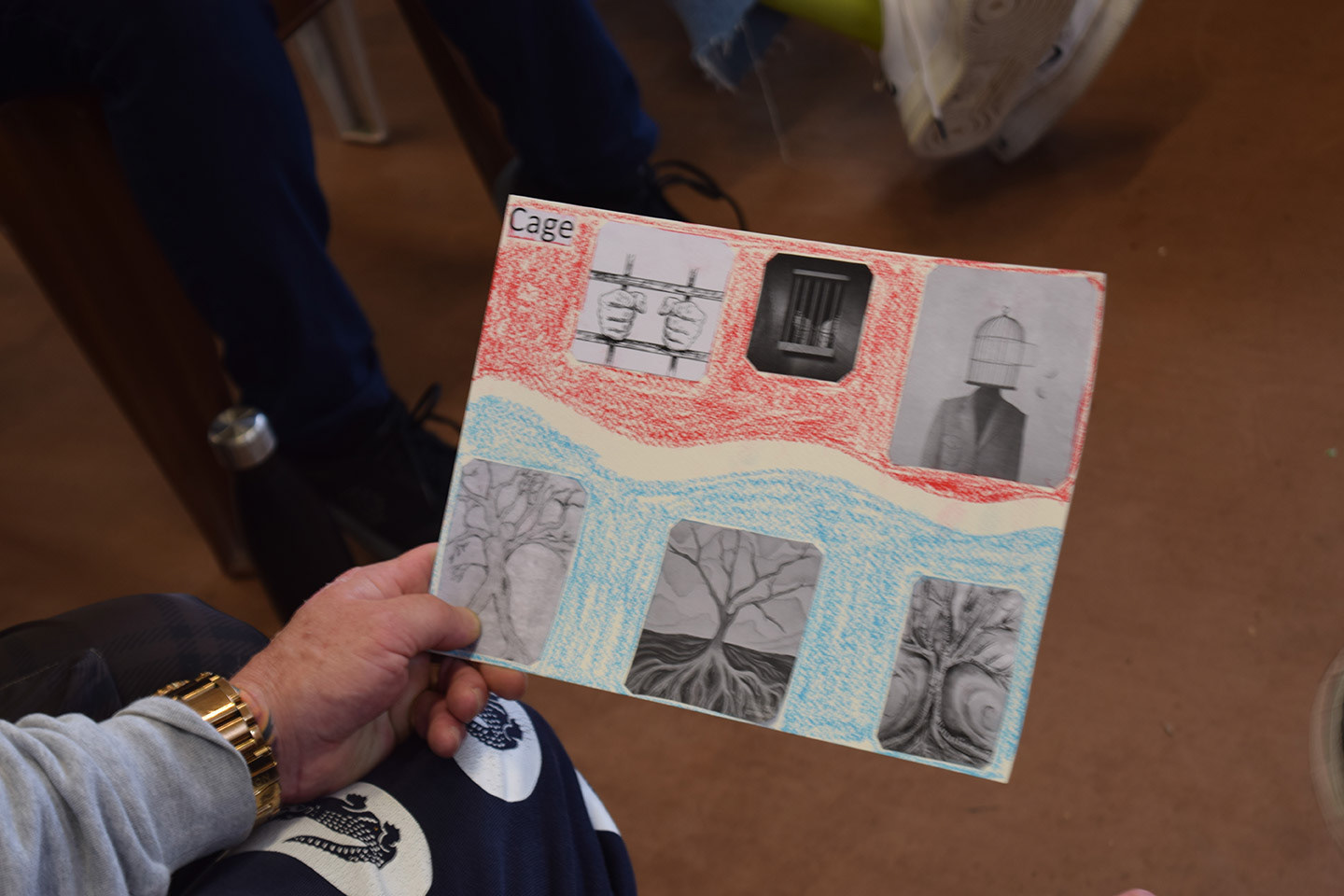

Drawing change, using colour and symbols to describe experience

While participants did not have any experience of process art, they readily adopted the practice and ably used colour, mark- and symbol-making to express themselves. Their art works, understood as artefacts lifted out of subjective consciousness, were used as tools of reflection. They offered the ability to gain space from contents of the inner landscape. As one of the participants said, “Yeah, just your choice of colours, I think they have their own message in the choice of colours. Sometimes, angry, sad, yellow, black, like that in itself, shows where you're at emotionally.” Elaborating on this when speaking about his use of colour in his ‘layers’ art work, this participant said:

That yellow is the sunshine from early childhood, it was very happy and bright for me. I remember mum cooking all the time, and baking and stuff like that, and always around Nan. But when I got to about seven, it started to get real dark and blue - beatings and sexual abuse started happening to me, and that went on for a lot of years, and then I got to this stage, which is red and green and black. That represents anger, hatred, bitterness, torture, lots of things, feelings of wanting to hurt people. Then there are the green lines for jail and that's my attempt at barbed wire. It represents jail and all the arguments I've seen in jail, all the things wrong with the system, never listening, not teaching us anything - the revolving door system. Then the top layer is orange and yellow and bright colours red, and that represents my happiness, where I am today.

For another participant colour and mark making offered a means to describe a practice he was using to better cope with his life. He speaks about a zig zagging line he drew to illustrate the reading from a heart monitor, which described the ‘ups and downs’ of life, and a patch of blue, which he placed in the middle of his art work to express balance. He explains that the line is, “like a wave of feelings, and the blue, it's kind of sort of your goal is to stay in the middle not get angry and go up to the top.” Further, the blue as a state of balance represents his realization that he’d “had enough, had enough of the whole system, and realizing that the war’s over, and it's not the life I want to live no more.” This participant also began to quickly build on his repertoire of art methods where, for example, he used different shades of orange to represent various intensities of anger, and shades of blue for varieties of peacefulness. Describing this he said, “that's why I did the orange, because there’s different volumes of anger. And then same thing again, with the dark and the light blue.”

Outcomes and Realisations

Art is a transformational act of critical consciousness. Not only is art the making of things; it also awakens new ways of thinking and learning that things can change (Kapitan et al., 2011, p. 64).

Reflecting on their experience of the workshop participants spoke of ways the art making was a useful, reflective, and therapeutic practice. As one participant said, “I'm just more aware of how it's been and what I've been through, and where I'm at, yeah.” The therapeutic benefit was described by this participant, as ‘all the baggage dropping off’:

And I had no expectation of the day of I didn't think I was gonna learn anything, to be honest. And then once we started doing those exercises, I started to get really interested in it, and I put everything I could into every one of those bits of art, because as I did each one, I was more drawn into the process. And I got to learn through art that I can get my shit out onto paper and feel relieved and its just another way of dropping all the baggage from your shoulders. And I was so energetic after it and I had to go home and do some more art, and then do meditation to calm down.

For some participants the process art practice led to realizations about how they’d been negatively impacted by imprisonment. They found, in some cases, that experience of imprisonment remained inside of them. Describing this, one of the participants said:

I think, that no matter how many years ago you were in jail, it’s something that will always be there. Especially the older guys, because some of those boys came up from a young age in foster care and homes, brutal, brutal homes, and they used to get beatings in jail, so it does stick with you.

For some participants the sense of always been watched, or always being on guard, stayed with them. As one participant said, “Yeah, like I realized that a lot of my behaviour, like watching myself is because, I always think I'm being watched, watching my movements, watching the way I behave, sometimes, being socially awkward. Being around people I’m constantly having to be apprehensive of who is around me. So, a lot of things do stick.” Another participant described a similar kind of anxiety saying:

I might think I'm cool, I might make my coffee and walk around my home, or I'll be in the mall, and I'll get a little bit weirded out sometimes. I still always look behind me. I don't like being put in a little room because it reminds me of being put in small cells, or waiting rooms in the jail. Really cold air conditioning reminds me, if there's ever a really loud cold air con near me.

Section 2 in conclusion

Participants came to the workshop for different reasons, and there were parts of the workshop they enjoyed and others they struggled with. Some were initially hesitant about using process art but all engaged with it, and quickly developed unique ways of using it. They also found that their art works acted as reflective tools, which were pivotal in re-examining aspects of their lives. In some cases, participants began to address ways they had been negatively impacted by imprisonment.

These rehabilitative outcomes are confirmed by scholars such as Clements (2004); Littman & Silva, 2020, and Williams (2016).

References:

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2024. Health of people in prison. Canberra, Australia:

Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-in-prison

Cheney, J. (1997). Suspending normal prison taboos through the arts in prison psychiatric setting. In D. Gussak & E. Virshup (Eds.), Drawing time: Art therapy in prisons and other correctional settings (pp. 87-98). Chicago, USA: Magnlia Street Publishers.

Clements, P. (2004). The rehabilitative role of arts education in prison: Accommodation or enlightenment. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 23(2), 169-178.

Cox, A., & Gelsthorpe, L. (2012). Creative encounters: Whatever happened to the arts in prisons? In L. K. Cheliotis (Ed.), The arts of imprisonment: Control, resistance, and empowerment (pp. 257-275). Hampshire, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

De Witte, M., Orkibi, H., Zarate, R., Karkou, V., Sajnani, N., Malhotra, B., . . . Koch, S. C. (2021). From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-27.

Edwards, S. (1994). Out of line: Art therapy with vulnerable prisoners. In M. Libmann (Ed.), Art therapy with offenders (pp. 121-143). Bristol, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd.

Johnson, H. (2008). A place for art in prisons: Art as a tool for rehabilitation and management. Southwest Journal of Criminal Justice, 5(2), 100-120.

Kapitan, L., Litell, M., & Torres, A. (2011). Creative art therapy in a community's participatory research and social transformation. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 28(2), 64-73.

Kelly, M. (2022). Carceral aesthetics justified. African American Review, 55(4), 287-301.

Littman, D. M., & Silva, S. M. (2020). Prison arts program outcomes (1974-). Journal of Correctional Education, 71(3), 54-82.

Schouten, K., de Niet, G. J., Knipscheer, J. W., LKleber, R. J., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. (2015). The effectiveness of art therapy in the treatment of traumatized adults: A systematic review on art therapy and trauma. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 16(2), 220-228.

Seidel, S., Tishman, S., Winner, E., Hetland, L., & Palmer, P. (2009). The qualities of quality: Understanding excellence in art education. MA, USA: Harvard Graduate School of Education, Project Zero, 1-126

Slayton, S. C., D'Archer, J., & Kaplan, F. (2010). Outcome studies on the efficacy of art therapy: A review of findings. Art Therapy, 27(3), 108-118.

Visse, M., Hansen, F., & Leget, C. (2019). The unsayable in arts-based research: On the praxis of life itself. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1-13.

Williams, R. M. (2016). Teaching and learning: The pedagogy of arts. In L. K. Cheliotis (Ed.), The arts of imprisonment: Control, resistance and empowerment. Oxon, Uk & New York, N. Y., USA: Routledge.

Woodgate, R. L., Tennent, P., Barriage, S., & Legras, N. (2020). The lived experience of anxiety and the many facets of pain: A qualitative, arts-based approach. Canadian Journal of Pain, 4(3), 6-18.